Industry Alum Pays It Forward through Physics Education Outreach

January 12, 2021 | By Cynthia Dillon

An exemplary arc of a physics student’s journey at UC San Diego can be tracked in the career of Larry Woolf. The technical fellow and sciences manager at General Atomics (GA), Woolf graduated with a PhD in physics from the university in 1980. He traveled to the east coast for his postdoctoral fellowship only to return to San Diego to accept a role at GA. Nearly 40 years and several different jobs within the company later, he is helping current physics students track their educational and career journeys—just like Distinguished Professor of Physics and Chair of the department Brian Maple did for him.

“In terms of who I am and how I got my job, he is really key,” said Woolf. “I owe Brian Maple the opportunity for getting my job at GA, where things have worked out well.”

General Atomics Technical Fellow and Sciences Manager Larry Woolf (PhD, ’80; physics). Photo courtesy of Larry Woolf.

General Atomics Technical Fellow and Sciences Manager Larry Woolf (PhD, ’80; physics). Photo courtesy of Larry Woolf.

The industry partner reconnected with the university a couple of years ago by helping to organize a celebration of his thesis professor’s 50 years on campus. This put him in touch with efforts to establish the Student Success Center, sparking his interest in helping it succeed. His participation has yielded support for the Dean’s Undergraduate Summer Research Award Program, which funds 10 undergraduate research fellowships for 10 weeks each summer.

“It’s nice to play the liaison role in connecting UC San Diego to a company,” said Woolf, who also serves as President and Chairman of the Board of the General Atomics Sciences Education Foundation.

For Woolf, the thread of consistency in his many roles over the years at GA has been the development of advanced materials—from working on energy conversion systems and graphite fibers to thin film coatings and superconducting wire.

“When you’re at a company, you’re constantly challenged to work on a number of different projects and almost all of them are different in some way. So it can be a very big change from what you’ve learned in school. Nevertheless they are all challenges that involve you thinking about what is the basic technology, what do I have to do to solve this problem, and then you have to execute the solution to that problem,” said Woolf. “When you’re in industry you become self-taught to learn whatever it is you need to be successful in your program.”

The nexus of industry and education

According to Woolf, industry differs from the university, where students determine the work they want to do.

“At university, you determine what you want to work on. In industry, you have some say in the matter, but often you have a contract—either an internal contract or an external contract—to develop something advanced—something no one has ever done before. And you have to do that under the constraints of funding, time, resources of your company, the people, the laboratory, the facilities and the things you have available,” said Woolf. “I find it very challenging—a different challenge than doing basic research—but I find it a really exciting challenge.”

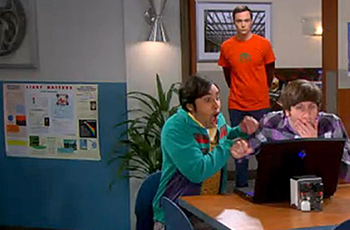

One of Larry Woolf’s educational posters adorns the set of the Big Bang Theory (all episodes available on HBO Max). Image courtesy of Larry Woolf, with permission from Warner Bros.

One of Larry Woolf’s educational posters adorns the set of the Big Bang Theory (all episodes available on HBO Max). Image courtesy of Larry Woolf, with permission from Warner Bros.

Woolf credits the owners of GA, the Blue family, with a company culture that has earned the appreciation of its employees and stakeholders alike. “It’s a private company, which is very different from a publicly traded company. The owner’s personality is reflected on how a company operates, and we have a terrific owner.”

Woolf said he takes this same approach into the education world. “I realize that it’s important to give back to the community, and it is also incredibly rewarding. As rewarding as my career has been, it has been equally rewarding in the education activities I’ve become involved with.”

He acknowledged that while not always the norm in industry, there are opportunities to get involved in education outreach. For example, he has participated in developing or reviewing K-graduate school and national laboratory programs with the National Science Foundation (NSF), the American Physical Society (APS) and curriculum development companies. All are as equally challenging and rewarding as his technical career, he said.

“My first venture into education outreach was in 1992, when GA decided that it wanted to get the company more involved in outreach. Its guidepost for that was what the Salk Institute had done with outreach. Neal Blue’s wife Anne helped start the program, along with Pat Winter, who was well known in San Diego education circles. They partnered with San Diego city schools and the county office of education,” explained Woolf, adding that teams of middle and high school teachers paired up with teams of GA scientists and engineers. “Together they developed five different educational modules aligned with areas of the company’s expertise. After developing the modules, the teams gave workshops to teachers in the San Diego area and beyond. That was the beginning.”

After completing the materials science education module and leading associated workshops, Woolf was inspired to create another module. This led to an invitation for his participation in a five-day teaching education workshop hosted by the APS to train scientists in how to get involved with K-6 elementary education. His participation in the workshop introduced him to current efforts in science education, which motivated him to get more involved.

“Because of the connections made there, I was invited to take part in NSF-funded science education activities, which led to more NSF involvement and to becoming a curriculum advisor for middle school and high school NSF-funded curriculum programs, which then led to my role in developing posters and other committee involvement,” said Woolf, adding that the posters typically are taken to events, after which middle-school and high-school students take them home, probably to put up in their rooms. “It is very rewarding because you know that’s going to inspire that student.”

Woolf has since written many education modules from Seeing the Light: The Physics and Materials Science of the Incandescent Light Bulb and Line of Resistance: Using a Graphite Pencil to Explore the Electrical Properties of Materials and Circuits, to Staying Alive: The Physics, Mathematics, and Engineering of Safe Driving and The Seasons: A Tale of the Sun, Earth, and Two Cities, to name a few.

Woolf initiated and manages the GA Scientists/Engineers Supporting Science/Engineering for Students (GASSSS) Program, through which more than 600 employees have impacted tens of thousands of students with their individually determined outreach activities. Before the pandemic, employees visited K-12 classrooms to perform the activities with STEM-related materials, supported by the company with more than $150,000. During the pandemic, GA employees have been performing the outreach remotely via Zoom.

Larry Woolf, during the earlier days of his GA education outreach instruction, presenting workshops during APS Teacher's Day. Photo by Edward Lee.

Larry Woolf, during the earlier days of his GA education outreach instruction, presenting workshops during APS Teacher's Day. Photo by Edward Lee.

Woolf says that what satisfies him about staying involved with education outreach is that he’s good at it. “When you’re good at something, it’s fun to do it. I find I can make a difference. I present a perspective of someone from industry who is not your standard person from academia,” explained Woolf. “I bring a combined set of knowledge from two different worlds—industry and academia—and I find that I have all this knowledge and experience in these two different worlds. I feel that it’s my duty, along with all positive reinforcements, to do it.”

The ‘Big Bang’ impact

Woolf’s mark extends beyond education outreach programs. His leadership also includes setting goals for national physics education through the APS and the American Association of Physics Teachers (AAPT) Phys21 Project, which helps prepare students for careers; its report was distributed to every physics department chair in the country. When chairing an education committee at the APS, in fact, Woolf’s goal was to organize sessions at national meetings.

“There was a national meeting in the Los Angeles area, so I called a professor at UCLA, who was a technical advisor for the “Big Bang Theory” television series, to ask him to give a talk about educating and exciting the public about physics. He encouraged me to get one of the creators of the show to talk instead. The professor gave me the contact of the show’s co-creator, Bill Prady, and I asked him to participate in the education session and he did,” said Woolf, adding that ultimately he ended up asking to be on the show. His wish was granted, and off he went to the studio in Burbank where he took part in three rehearsals.

“I was told to bring four shirts, specific colors only to blend in. When I got there, the set people said no logos could be on the shirts and all the shirts that I had brought had logos, so I had to wear the shirt I had on, which was the wrong color. So they threw a blue blazer over it. Then I held the newspaper at the first rehearsal incorrectly because I lifted it partially,” explained Woolf. “I failed wardrobe and reading a newspaper, so I was moved—put in ‘detention’ at the back of the set. But Bill Prady stepped in and moved me right next to the actors – putting me on screen much of that episode!

While at the studio, Woolf said he noticed science posters on the set and in the building. So seeing an opportunity, he offered to send his own posters. The show used one of them five different times during filming.

“One of the recommendations I give to students is, if things aren’t working out for you at a certain place, think about moving. But if things are working out for you well, think really carefully about leaving,” he said. “If there’s an interesting opportunity, never say no.”

In the end, Woolf said there is always a kernel of physics in everything he does.

“It’s always fun to understand what that kernel is and understand this is the basic physics of what I’m doing. Often what I’m doing has that physics in it, but solving the problem involves all the other externalities that you need to bring to bear to solve that problem—most of them are material related or understanding other people. The engineering of ‘that physics problem’ into a useful product is really the key to being successful.”