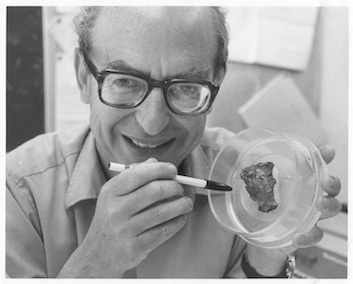

Jim Arnold, founding chemistry chair, 1923-2012

James R. Arnold, founding chairman of UC San Diego’s chemistry department and first director of the California Space Institute whose contributions to science spanned the study of cosmic rays to the future of manned space flight, died Friday, January 6. He was 88.

James R. Arnold, founding chairman of UC San Diego’s chemistry department and first director of the California Space Institute whose contributions to science spanned the study of cosmic rays to the future of manned space flight, died Friday, January 6. He was 88.

“Jim Arnold truly was a visionary scientist who found creative ways of looking at a broad range of problems, terrestrial and extraterrestrial,” said Mark Thiemens, Dean of the Division of Physical Sciences.

A longtime consultant to NASA, Arnold helped to set science priorities for missions, including the Apollo flights to the moon. He first served on a NASA committee in 1959, just three months after the space agency was established.

“I have known Jim Arnold for over 60 years. He was a dedicated and imaginative scientist,” said Gerald Wasserburg, emeritus professor of geology and geophysics at Caltech. “He was a lover of the Pogo comic strip and of Buck Rogers who ignited his passion for shooting people into space and colonizing it.”

Arnold and Wasserburg, along with Paul Gast and Bob Walker, whom their colleagues called the “Four Horsemen,” helped to establish the national lunar sample research program and fostered its remarkable contributions to planetary science over the decades since Apollo 11.

Arnold was in Houston for the arrival of the first lunar samples and carried some of them back to his laboratory at UC San Diego where his group studied them, sometimes while watching astronauts on subsequent missions on television as they collected the rocks Arnold’s group would study next.

“The excitement of it - to hold something that’s from the moon,” said Candace Kohl, a graduate student who pulverized the rock surfaces with a dental drill as part of her study. “You would have to collect the moon dust off your fingers.”

Over more than two decades, Arnold traced the history of moon rocks’ bombardment by cosmic rays and extended our record of the energy output of the Sun by millions of years.

Over more than two decades, Arnold traced the history of moon rocks’ bombardment by cosmic rays and extended our record of the energy output of the Sun by millions of years.

He established long and fruitful partnerships with other scientists, including Devendra Lal, now an emeritus professor at Scripps Institution of Oceanography. “Jim always had intelligent ideas. It was one of my nicest collaborations,” Lal said. “He was my friend for 50 years.”

Masatake Honda, a cosmochemist now retired from the University of Tokyo, remembers a life-changing conversation with Arnold. “He said he was going to move to San Diego, California” and invited Honda to join him there. “I would not have been able to be a part of countless discoveries made at UCSD. I must thank him, for this single lunch time conversation changed the entire course of my career,” Honda said. “Arnold will never disappear from my memory.”

In 1970, NASA recognized Arnold’s work with an “Exceptional Scientific Achievement” medal. Arnold also received the Department of Energy’s E.O. Lawrence Award in chemistry and metallurgy.

Cosmic rays leave traces in meteorites as well, a record of “how long they have been a rock in space,” Arnold told a reporter for the Los Angeles Times. For his work on the ages and origins of meteorites, Arnold received the Meteoritical Society’s Leonard Medal in 1976.

Arnold’s scientific work began with the study of the nuclei of chemical elements. He earned three degrees in chemistry from Princeton University, culminating in a Ph.D. awarded in 1946 for his work on the Manhattan Project.

He had deep concerns over the threat of nuclear fallout and was a thoughtful contributor to the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists from its foundation.

After completing his degrees, Arnold joined Willard Libby’s group at the University of Chicago’s Institute for Nuclear Studies, where he helped to develop a method still used by archaeologists and paleontologists for dating once-living things using radioactive carbon. The work touched on a lifelong interest in the human past that Arnold inherited from his father, an amateur Egyptologist. Arnold spent three years at Chicago as an assistant professor.

When he returned to Princeton as a faculty member in 1955, Arnold expanded that research to look at the effects of cosmic rays on meteorites using isotopes that decay far more slowly, over millions of years, recording the age of much older rocks.

Arnold and colleagues discovered radioactive isotopes of beryllium that are produced by cosmic rays. One of them, beryllium-10 with a half-life of 1.36 million years, can be used to trace long histories of rocks and soils.

Roger Revelle recruited Arnold to be among the first faculty to join the fledgling UC San Diego campus in 1958. In 1960 Arnold became the founding chairman of the chemistry department and was a popular teacher in those early days of the campus.

Arnold was a member of the National Academy of Sciences and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

In 1980, Eleanor Helin and Eugene Shoemaker named an 8-mile-wide asteroid that they discovered “2143 Jimarnold” because “he’s a fine friend and colleague whose work laid the groundwork for ours,” they told a writer for UC San Diego at the time.

Arnold founded the California Space Institute in 1979 to foster innovation in space research. As director for the first 10 years, he identified promising young scientists and encouraged their risk-taking work. The annual Jim Arnold Lecture recognizes his contribution by inviting an interesting speaker who has made significant contributions to chemistry and the space sciences to campus each spring.

Arnold held the Harold Urey Chair in Chemistry, named in honor of the father of planetary science, from 1983 until he retired in 1993.

Arnold was an active World Federalist and met his wife, Louise, at a federalist conference in 1950. They married in 1952. Arnold is survived by Louise Arnold, their sons Bob, Ted and Ken, and their families.